YOU MAY HAVE THOUGHT that the award for Longest String Quartet Made Up of Slow Movements was won by Shostakovich for his final work in that form, but Haydn nabbed it two centuries earlier when he arranged his orchestral work “The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross” for that instrumentation.

|

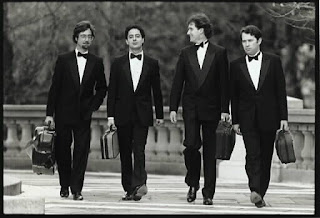

| The Emerson Quartet: Now |

This was the ensemble’s 27th appearance in the College’s renowned concert series, itself in its 38th year, and a wonderful kickoff to the season.

Haydn wrote the piece in response to a commission circa 1786, and a year later his quartet arrangement appeared. Or maybe it wasn’t his: The voicings betray haste and/or incompetence, so the Emersons touched up the score using the original version as a guide.

A gentle introduction leads to seven slow sections, each a wordless setting of brief texts drawn from the Gospels of Matthew, Luke and John. To eighteenth-century ears, these must have sounded much more plangent than what we’re accustomed to hearing – musical depictions of anguish have come a long way, beginning right away with Beethoven.

Nevertheless, and taken on their own terms, these movements (sonatas, as Haydn termed them) throb with unique intensity, relying considerably upon passionate melodies for much of the effect. There’s also a compelling architecture to each section, bringing it to a satisfying climax and denouement.

Much of the accompaniment texture is achieved through ostinato passages, repeated notes of a chord that provide an effective pulse. The Emerson Quartet players skillfully varied the sound of all that repetition with a variety of bowing, sometimes separating the notes, sometimes playing several with a single bow with varying amounts of accent.

Add to that their always faultless technical ease and ensemble voice, and it was an intense, if low-key, experience – one that contrasted nicely with Dvořák’s “American” Quartet – a piece the Czech composer wrote while in the U.S. in 1893.

There’s plenty of room for debate on just how much the composer borrowed from various Native American sources (including birdsong); the lively four-movement work could have been written by nobody else, and there’s a Bohemian feel twined in with everything else.

And what a testament to how far the language of quartet-playing had advanced in a century! Contrast, for example, the pizzicato effects in the sixth movement of the Haydn to Dvořák’s Lento, where it’s a more tightly integrated technique.

This is a piece on every quartet’s greatest hits list, and the Emersons – violinists Philip Setzer and Eugene Drucker, violist Lawrence Dutton and cellist David Finckel – played it with the passion that comes from loving familiarity.

Per their custom, Setzer and Drucker swapped first violin, on a movement-by-movement basis in the Haydn, also configuring their positioning to suit the particular work. Union College’s Memorial Chapel offers a glorious reinforcement to their sound, so it was as satisfying as concertgoing gets.

Emerson Quartet

Union College Memorial Chapel, Oct. 18, 2009

– Metroland Magazine, 22 October 2009

CHAMBER MUSIC CONCERTS may only draw a special-interest subset of the classical crowd, but that subset has grown to support an ever-increasing number of professional chamber groups over the past few decades.

Making it a challenge for any of those groups to establish a performing identity. The Emerson Quartet, a favorite with the local audience, performed Wednesday evening at Union College’s Memorial Chapel and proved that it is just such an identity that sets this group apart.

|

| The Emerson Quartet: Then |

It takes a lot of guts to submerge your individual playing voice into the voice of an ensemble, and these performers are obviously extremely skilled individuals. Anyway, the term “submerge” isn’t appropriate because virtuosity is a hallmark of the confluence of the four.

Which is important for a piece like Prokofiev’s Quartet No. 1 in B minor to succeed. By no means a staple of the quartet repertory, this is nevertheless a fascinating example of the composer’s lyrical percussiveness. The work weaves between accompanied solos and full ensemble writing, with the nervous aggressiveness of the first two movements calmed by the plaintive serenade of the third.

Eugene Drucker played first violin for this work (and the Mozart quartet that followed) and triumphed over the nightmare solo writing; similarly, the solo qualities of the rest of the group (violinist Philip Setzer, violist Lawrence Dutton and cellist David Finckel) were put to excellent use.

The Prokofiev quartet has moments in which it seems to throb and sigh, like a berserk accordion, and these moments brought out the Emerson Quartet’s powerful unity, playing not just as one instrumentalist, but as one with compelling, passionate ideas.

Can this passion be too overpowering? Mozart’s Quartet in E-flat major, K. 428, is one of a set which the composer considered particularly accomplished. As played by the Emersons, it has a boisterousness that you wouldn’t expect – at least based on the performance of other quartets. The dynamic range is wider, the attacks have more crunch. This isn’t drawing room Mozart: it’s too high-spirited. And it anticipated the treatment Beethoven would receive at the finish of the concert.

The pairing of Bartók and Beethoven quartets is a great musical lesson, although it wasn’t just academics that made it so felicitous a combination. Both pushed the quartet form in unprecedented directions while keeping roots in then-current traditions.

The Quartet No. 3 by Bartók is one of his most austere works, a study in fragmented lyricism that puts the players through a hellish journey. Setzer took the first violin chair for this part of the concert, but it would be hard to say just who had the tougher part: in the Bartók quartets (he wrote six) you’re called upon to do almost anything.

By this point it was like seeing a familiar repertory company in a new, unfamiliar work. The voices were well known and thus made it a more accommodating experience, but the piece doesn’t give up its mysteries too easily.

Anyone familiar with the Bartók Quartet No. 3 got the added treat of witnessing this ensemble having an obviously enjoyable time with it even as they satisfied its requirements.

Beethoven’s Quartet No. 11 in F minor, composer-dubbed “Quartetto Serioso,” was the most familiar work on the program but it, too, got an unexpected treatment. These players take movement markings seriously, and when an Allegro is meant to be played con brio, they brio the thing.

Of course, it takes more than sheer speed to make a performance work, and each movement of the Beethoven was shaped with care: well thought-out, well-played, beautifully realized.

The Emerson Quartet has become a staple of this concert series; when it was announced that they would return next season the audience cheered.

The next concert this season is a performance by the Takacs String Quartet at 8 p.m. April 28, in a program of music by Haydn, Beethoven and Zsolt Durkó.

Emerson Quartet

Union College Memorial Chapel, 5 April 1989

– Schenectady Daily Gazette, 7 April 1989

No comments:

Post a Comment