I take only one very small credit in all this. As far as I’m concerned, the DNA business is the luck of the draw. She grew up in a family in which food is over-celebrated, by which I mean over-consumed, and she showed the effects of that when younger.

I take only one very small credit in all this. As far as I’m concerned, the DNA business is the luck of the draw. She grew up in a family in which food is over-celebrated, by which I mean over-consumed, and she showed the effects of that when younger.But Lily took that situation in hand, changed her diet, (literally) exercised her butt off, and reshaped herself into the young woman you see today.

She grew up with cameras frequently aimed her way, courtesy of me, who was as fanatical as any father in documenting her early years. That those documents exist on formats (film, videotape) now obsolete testifies to technology’s relentless changes and therefore protects her from being reminded too much of her toddlerhood.

The one credit I claim for her modeling achievements dates back to those earliest snapshots, or at least back to when she could understand a photographer’s direction. “Make faces!” I would tell her. “Roll your eyes! Mug!”

I had an ulterior motive. I was undermining any possibility that she might follow in my footsteps – who knows how slyly heredity might work? – and take it upon herself to ruin the photos. Because there exists almost no images of me as a kid that I somehow didn’t mess up.

My father struggled to still-capture his brood, wielding his vintage (and very collectible) Nikon with a keen eye undaunted by its unfriendly range-finder focusing, its you-set-‘em aperture and shutter speed selections, its overlarge bulb-hungry flash. All he wanted – I know this now – was a reasonable keepsake capturing his brood. What he got – I confess with embarrassment – was an Ektachrome record of my facial antics.

It does me no credit to note that I became a master mug-smith. Soon enough I realized that he wouldn’t push that shutter button until my face assumed some aspect of normalcy. So I learned two important things. First was that very little contortion was needed to screw up a picture. A quick eye-widen, a lip curl, a nostrils flare would do it. Second: keep an eye on his trigger finger. Lull him into thinking you’re about to cooperate, and once that digit begins its descent, go into the mug-face. And go right out of it again! Properly done, the moment would pass without notice – until the color slides came back from processing and my three-feet-high sneer sent my Dad into a fury.

It gets worse. As my younger brother and sister grew to understand that I was getting all kinds of attention (however negative) for these efforts, they joined in the fray. Perhaps not with the ruthlessness I employed, but enough to learn the tricks of muggery.

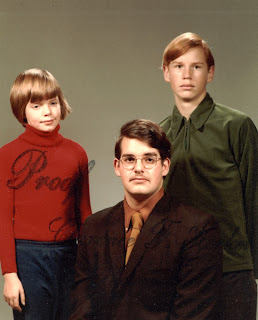

The culmination of this effort came towards the end of 1972. I was 16; my brother David was about to turn 15; my sister Jennifer was nine. My father had a new job that would move him from Ridgefield, Connecticut, where we’d lived for nearly a decade, to the northwestern suburbs of Chicago. I was a senior in high school and a troublesome teen, so my parents took advantage of an opportunity to let me remain and graduate there. Which meant it was time for a family portrait.

A portrait of the kids, at least. The last time we’d sat for a professional photograph was in 1960, when our next-door neighbor in Glen Rock, New Jersey, posed David and me in his studio after my mother traumatically dressed us in suit-jackets and skinny bow ties. Only a decade and a half later did I learn that this photographer, whose name was Duncan Butler, used to hang around such places as the Apollo Theater in Harlem, photographing jazz greats, responsible for the Billie Holiday images on the cover of a prized LP set.

Now the three of us were herded into the downtown-Ridgefield studio of Clarence Korker, the town’s respected portrait artist. We didn’t plan it, we didn’t speak to one another as the photos were taken, and yet . . .

The usual Friday activity of a number of the town’s high-school teachers was to assemble at a downtown pub and celebrate the coming weekend with a few soul-calming rounds. “Your mother came roaring in,” one of my teachers told me not long after, “and waved this set of photographs in our faces, yelling, ‘Do you see what those little shits did?’”

One example is posted at the top of this essay. You’ll find the rest of them at the end. It’s not as if every one of us mugged in every one of the photos. More insidiously, the series suggests that we worked in unconscious concert, spreading the offending expressions from kid to kid in each successive shot.

Characteristically of my mother, she chose what she considered the worst of them and had it enlarged to hang in her new living room.

. . . . As I’d hoped, my daughter eventually rebelled. “Do I have to make faces?” she asked one vacation day. “Can’t I just try to look normal?” And there you have my contribution. Anything beyond that is to her credit alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment